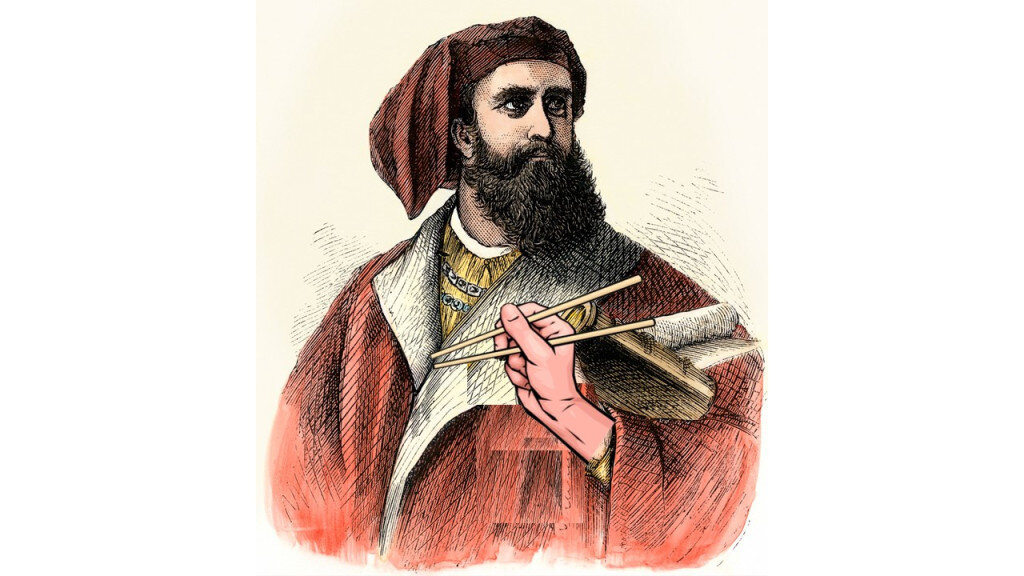

Marco Polo Introduced the Chinese to Chop Sticks

Years ago, I had an acquaintance who was from China. He insisted that the Chinese invented spaghetti. He believed in the myth that Macro Polo introduced Italians to it when he returned from his travels. It did not matter what I told him; he was told this all his life. So, as far he was concerned, it was the absolute truth. Remembering the adage attributed to Mark Twain, it’s easier to fool people than to convince them that they have been fooled, I gave up. Instead I told him that most people don’t know that Marco Polo introduced the Chinese to chopsticks.

Before I go much further, I should confess that I feel somewhat pretentious using the word pasta. Based on conversations I have had with other Italian-American kids of the 1950s and 1960s, many feel the same way. When I was a kid, I cannot think of a time when asking my mother what was for dinner, she would say pasta. It was either spaghetti or macaroni. When I hear medagons say pasta, I envision Silicon Valley hipsters with man-buns and ridiculous beards telling one another of their most recent culinary adventure; “Last night we had the most wonderful free-range seafood pasta with truffles and parmareggio cheese made from the milk of grass-fed albino Peruvian Alpacas.” It is imperative that the Alpacas be albino, makes the milk whiter.

I know I sound like an old curmudgeon, a cranky old man that says stuff like, “when I was a boy, we called it spaghetti, dag-gumbit!” But, when I was a boy, Wednesday was spaghetti night in Italian-American neighborhoods, not pasta night. Don’t get me wrong, the correct term is pasta, which in Italian means paste. The word is used in reference to not just spaghetti and macaroni, but to pastry or dough as well. When you make pasta, you roll out your dough, which is the paste stage, then cut it into appropriately sized strips or noodles.

This process, making and cutting dough, has not always been done in the most sanitary conditions. You can see in pictures of old Napoli where pasta was hung out in the open air of the streets to dry. Things weren’t any better in the United States. Maddalena Tirabassi in her essay Making space for Domesticity, describes the life of the Italian-American in Little Italy in early 1900s;

“Macaroni is made in every block of the Italian neighborhoods of New York,” one reformer reported. “In many streets, you will find three or four little shops in one block of houses, with macaroni drying in the doorways and windows. The front room is the shop, and the family living in the middle and rear rooms, and these are invariably overcrowded. The Italians not only have large families, but keep lodgers, and the front shop then becomes a sleeping and living apartment as well as other rooms. The paste is mixed and pressed by a machine into long strings, which are hung on a rack to dry… A child lay sick of diphtheria in the back room where the physician visited her. The father manufactured macaroni in the front adjoining room, and would go directly from holding the child in his arms to the macaroni machine, pulling the macaroni with his hands and hanging it over racks to dry.”

This may sound less than appetizing, but people were not all that concerned with hygiene in the old days. The way they ate pasta back then was to grab some spaghetti with their hands, tip their heads back, and let it all slide down their throat.

While Emily Post, the definer of proper etiquette, would have been shocked to see Italians eat their spaghetti this way, it has implications for those arbiters of what is proper Italian-American behavior. You know the group, the ones that tell us we must call it gravy and not sauce. They tell me that I am not an authentic Italian if I do anything other than twirl my spaghetti without a spoon. God forbid anyone should see my medagon wife who cuts hers with the side of her fork. The thing is, her sauce is fantastic, just about as good as my mother’s, so she could eat her pasta anyway she pleases.

While certainly all of this shows how much pasta is a part of Italian and Italian-American culture, it would be no more correct to say that it is the invention of the Italians than it is to say that it is of the Chinese. The reality is that when people face similar problems, they will very often independently find similar solutions. Pasta developed in Europe and China simultaneously, with no evidence that either influenced the other. The Romans are known to have eaten a lasagna type noodle called Laganum and the Greeks itrion. There is evidence that sheets of pasta were boiled in water as early as the third century. There are also many Italian stories from the middle ages that involve pasta.

If the Italians learned anything about pasta from anyone, it would have been the Arabs. Part of their influence on Italian culture was the introduction of dried pasta, something that became common by the tenth century, bear in mind Marco Polo did not return from his travels until the mid-1290s. Italian regions such as Sicily, Sardinia, and Liguria were involved in the manufacture and export of pasta beginning in the early Middle Ages.

Again, remembering what our good friend Mark Twain said, I doubt that this information will do any good in changing the minds of those who are most invested in the Marco Polo myth. However, some will listen to those who don’t just argue that Marco Polo introduced the Chinese to chopsticks. It has the same amount of truth.

For more on Italian and Italian-American culture, read my book Italianità, The Essence of Being Italian.