Canto 1: Lost and Afraid in Dante’s Wood

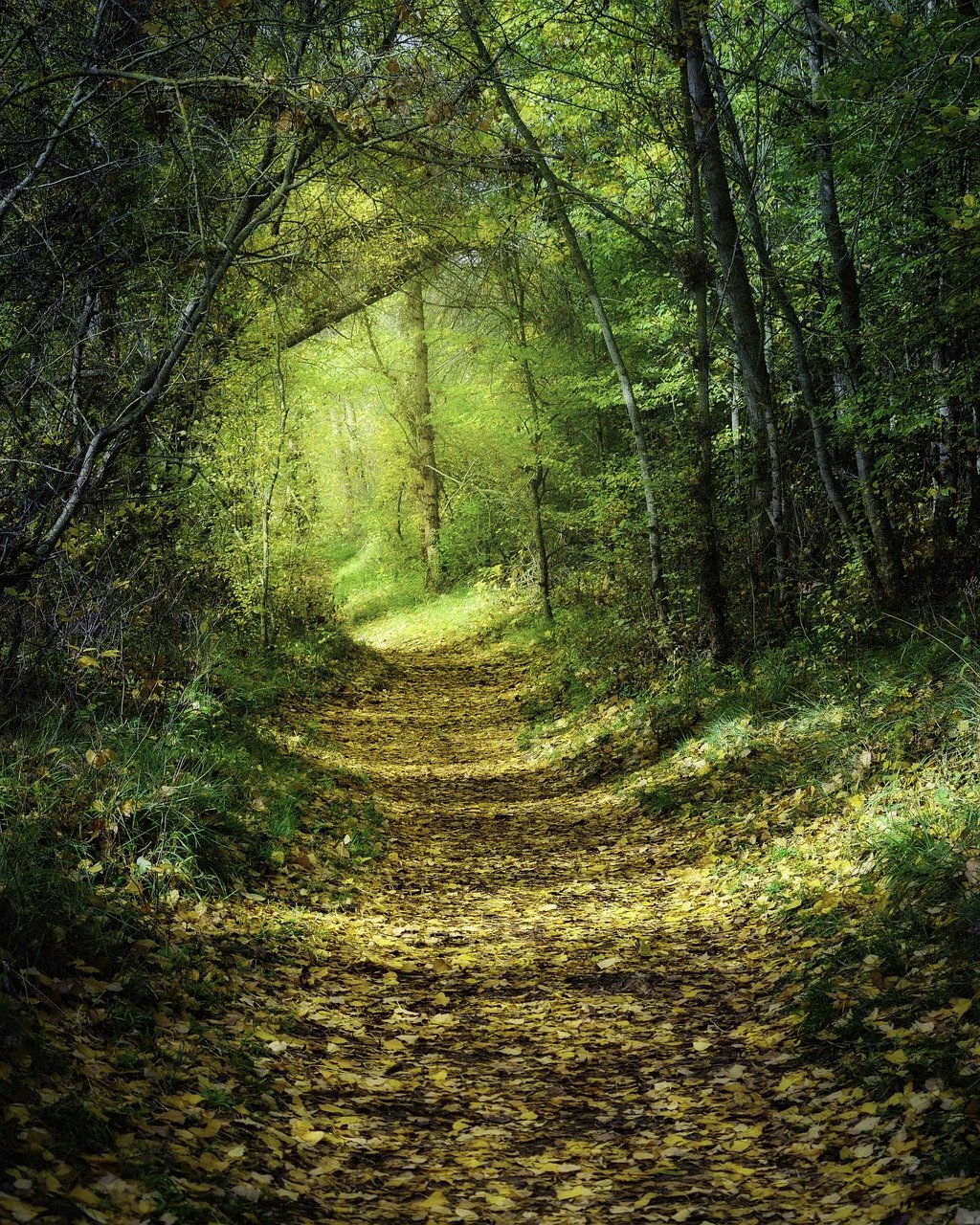

This past May, I was fortunate enough to walk the Camino de Santiago. One morning, I headed out a couple of hours before dawn, hoping to reach my destination before the sun became too strong. There was no moon, so it was very dark. If there were any stars, I could not see them through the canopy formed by the trees. Although I had a headlamp, walking through an inky black forest was unnerving. I worried about what might be hiding in a clump of bushes farther up the path. Worse yet, what was behind me? I started to sing, hoping to frighten anything that might be nearby. Then I wondered, would I be scaring off potential predators or simply telling them where to find their breakfast? Although sitting in my comfortable, well-lit library, I can now laugh, I was more flustered than I care to admit.

The experience made real to me the confusion and fear Dante must have felt in Canto 1 of the Inferno. I, like Dante, was a pilgrim alone in a dark wood. Even as I say this, I feel the comparison is unfair to Signore Alighieri. Dante was lost and in the dark. He did not have a GPS to guide his steps or a rechargeable LED headlamp to light his path. Yet, even with these advantages, I was still apprehensive. It was not my best morning on the Camino.

Is the Feast of Seven Fishes Italian

Canto 1: The Journey

Many have long described The Divine Comedy as the greatest work of Western literature. This acclaim is due, in part, to Dante making his journey from bondage to freedom personal to his readers. His poem reaches out and pulls us into the experience of his spiritual enlightenment.

Dante begins by telling us, “Midway in our life’s journey / I awoke to find myself lost in a dark wood.” The tension created between “our life’s journey” and “I awoke” is a subject of a great deal of speculation. What was the authorial intent? Why didn’t Dante simply write in the middle of my life’s journey, I awoke? We might brush off this conflict as sloppy writing, that Dante had intended no deeper meaning here, but I believe this would be a mistake. While I cannot say with any absolute authority what Dante had intended, I think there is a purpose in his choice of words. And, that purpose is an example of how Dante draws us into the poem from the very start.

Sauce, Gravy, or Dante? (Part 1)

In 1954, Giuseppe Prezzolini, Italian author and historian of Italian literature asked; “what is the glory of Dante compared to spaghetti?” He went on to observe “spaghetti has entered many American homes where the name of Dante is never pronounced.”

Sauce, Gravy, or Dante? (Part 2)

Dante Alighieri; author of The Divine Comedy, Father of the Italian Language, philosopher, theologian, statesman. In my previous post, I make the point that to truly understand Italian and Italian-American culture you need to understand Dante. That post focuses on Dante the poet, the author of The Divine Comedy.

The Feast of Seven Fishes, Why It is Important

For many Italian-Americans, the high point of Christmas is the Christmas Eve Feast of Seven Fishes. This custom, however, has a special added significance for me personally. It was my father’s last meal. On Christmas Eve 1977, after enjoying the traditional meal my mother had prepared, my father went to bed where he fell into a wakeless sleep. Since then, the Feast of the Seven Fishes was more than part of my Italian-American heritage, but a remembrance of my father.